Robin Buckley, IFS Icon

<Stranger Things spoilers disclaimer>

Hawkin’s favorite radio DJ, Robin Buckley, reflected on her first crush, a heartbreak, and gained a realization that quietly changed everything for her. She shares this with fellow Stranger Things co-star, Will Byers, in a tender moment this past season. It’s not dramatic or flashy, but the moment lingered with me because it named something many of us might be able to recognize: the fear of fully being ourselves, and the hope that someone else might make that fear go away.

As a clinical intern curious about Internal Family Systems (IFS), I was struck by how closely Robin’s monologue mirrors ideas we talk about in therapy quite often; the concept of “parts,” and the way in which we often seek outside of ourselves for safety, validation, or even answers that are already within. This is not as a clinical analysis, but a way to frame self-understanding, and the therapeutic language many people are just beginning to encounter. Robin’s realization isn’t just a coming-of-age moment, it’s therapeutic.

According to IFS, we all have ‘parts’ - parts that are not ‘bad’ or ‘broken’, but informative to who we are in the present. Each of us has a core self, that is calm, curious, and compassionate. IFS is not about getting rid of parts, it’s about being curious about them in order to understand why each part of us exists.

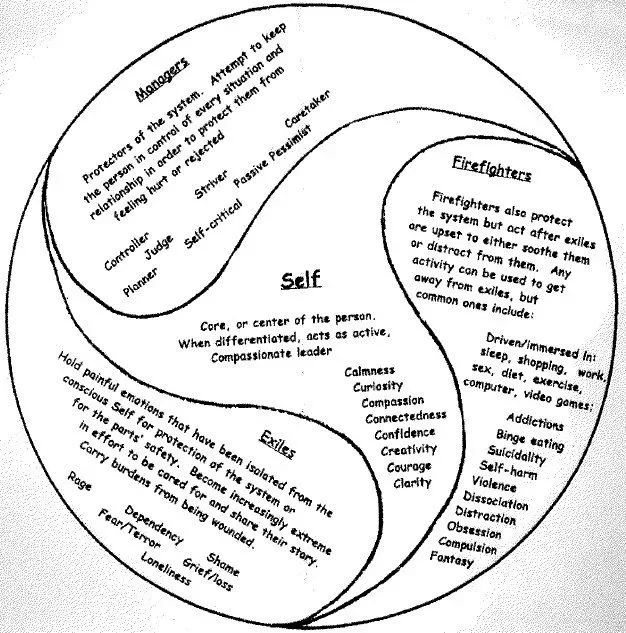

From an IFS viewpoint, our inner workings are less like a single narrator, and more like a cast of characters within us, all with a uniquely supportive purpose. At a high level, our internal co-stars are:

Managers: Protectors of the system. Proactive, controlling parts that try to keep life organized, predictable, and emotionally manageable by preventing situations that might trigger pain or vulnerability.

Firefighters: Also protect, but are reactive, urgency-driven and step in when pain breaks through. They often use distraction or numbing behaviors to quickly shut down emotional distress.

Exiles: Vulnerable parts of us that carry pain, shame, fear, or unmet needs. Often pushed out of awareness because they feel overwhelming or unsafe to hold.

Core Self: The grounded, compassionate center that isn’t a “part”, but is characterized by our inner self that exists with a sense of curiosity, calmness, clarity, and the ability to relate to our parts with understanding rather than fear.

“Because there was always this part of me that kind of scared me.”

Robin names a part of herself that felt deeply frightening to acknowledge beneath the surface, the exiles. A younger, vulnerable part that carries fear around being fully seen, accepted, or safe as her authentic self. This part carries emotional weight that felt too overwhelming to face alone. This fearful part isn’t something pathological or wrong; it’s a protective response.

“But I thought that if Tammy loved me, all of me… I wouldn’t be so scared anymore.”

In response to Robin’s fear, the manager steps in. The manager contains her vulnerability, and seems to believe that if Tammy Thompson loves her then there would be no fear. Instead of addressing the pain directly, the manager attempts to solve it (here, externally), around the idea that someone else’s love will make her “not so scared.” The manager isn’t misguided, it’s a part that is trying to prevent the exiles from being hurt by seeking safety wherever it seems most possible.

“My entire fantasy life with her, along with the rest of my life, pretty much imploded before my eyes. I mean, my grades plummeted. I got grounded. I had to stay home every weekend doing chores.”

Robin doesn’t explicitly describe impulsive or harmful numbing behaviors, but she does allude to emotional overwhelm and fantasy that often activates the firefighter. The sudden collapse of her fantasy and sense of safety - by way of Steve ‘The Hair’ Harrington - suggests her system flooded with pain after the manager’s strategy failed. When our distress breaks through its containment, firefighters emerge and work reactively to shut down that intensity.

“... and all of a sudden, I was looking at this little version of myself. And that little me, I could hardly recognize her. You know, she was so carefree and, like, fearless. She just loved every part of herself. And that’s when it hit me. It was never about Tone-deaf Tammy. It was always just about me. I was looking for answers in somebody else, but… I had all the answers. I just needed to stop being so goddamn scared. Scared of… who I really was. Once I did that, oh, I felt so free. It’s like I could fly, you know? Like, I could finally be…Rockin’ Robin.”

This moment of finding her core self is not “achieved”, but feels more like something remembered. This younger version of herself is not judgmental or critical. We hear a deep compassion in the way Robin speaks about this little version of herself, “carefree, fearless, loving every part of who she was”. Robin’s reflection isn’t frantic or defensive, it’s observant and curious.

Robin notices this younger self without trying to change her. There’s a sense of calm that allows insight to emerge naturally. From this calmness came clarity: the realization that it was never about anyone else, but her own relationship with herself.

When our core self is present, each individual part no longer has to work so hard, fear loosens its grip, and we gain capacity to hold our inner experiences with honesty and care.

Robin doesn’t erase her fear in this moment; she understands it, and that understanding allows her to feel free.

Robin’s story resonates not because it’s unique, but because it showcases a deeply human experience, especially for those who have learned, early on, that being fully themselves might come with risk. For many people in marginalized communities, fear isn’t just internal; it’s shaped by real experiences of rejection, invisibility, or harm. The parts that organize around safety, concealment, or self-protection often make profound sense in these contexts. Robin’s realization offers a gentle reminder that healing doesn’t require erasing those parts or forcing fear away, but meeting them with curiosity and compassion.

References

Steele, Connie. “Internal Family Systems Therapy.” Family Relations, vol. 45, no. 3, National Council on Family Relations, 1996, pp. 355–56, https://doi.org/10.2307/585517.

Stranger Things 5 | Robin’s Speech to Will (official clip) | Netflix